Open Data Maturity Report 2022: Countries’ perspectives on their open data policy

Monitoring actionable plans and practising iterative improvements make for good open data policy implementation

The Open Data Maturity (ODM) report provides an overview of the progress achieved by European countries as they push forward in creating the necessary conditions to make the most of open data. The concept of open data maturity in Europe is considered against four dimensions: quality, portal, policy, and impact.

The European Union formulated its European data strategy to create a single market for data to ensure global competitiveness and allow data to flow freely within the EU. At the same time, the European data strategy aims to empower the society with data while ensuring that European rules, such as privacy and data protection, are fully respected. To achieve this, there is a wide range of policies to be implemented; more precisely, open data policies that focus on generating value for the economy and society through the reuse of public sector information. Both EU Member States and non-EU countries implement national policies that make this happen. The open data maturity (ODM) report provides an overview of the progress achieved by European countries in implementing these policies and encouraging the reuse of public sector information.

This data story is the fourth in the 2022 ODM report series and dives deeply into how countries are performing on the policy dimension. The first data story announced the publication of the report and presented the overall results, the second data story discussed the quality dimension of the methodology and the third data story covered the portal dimension.

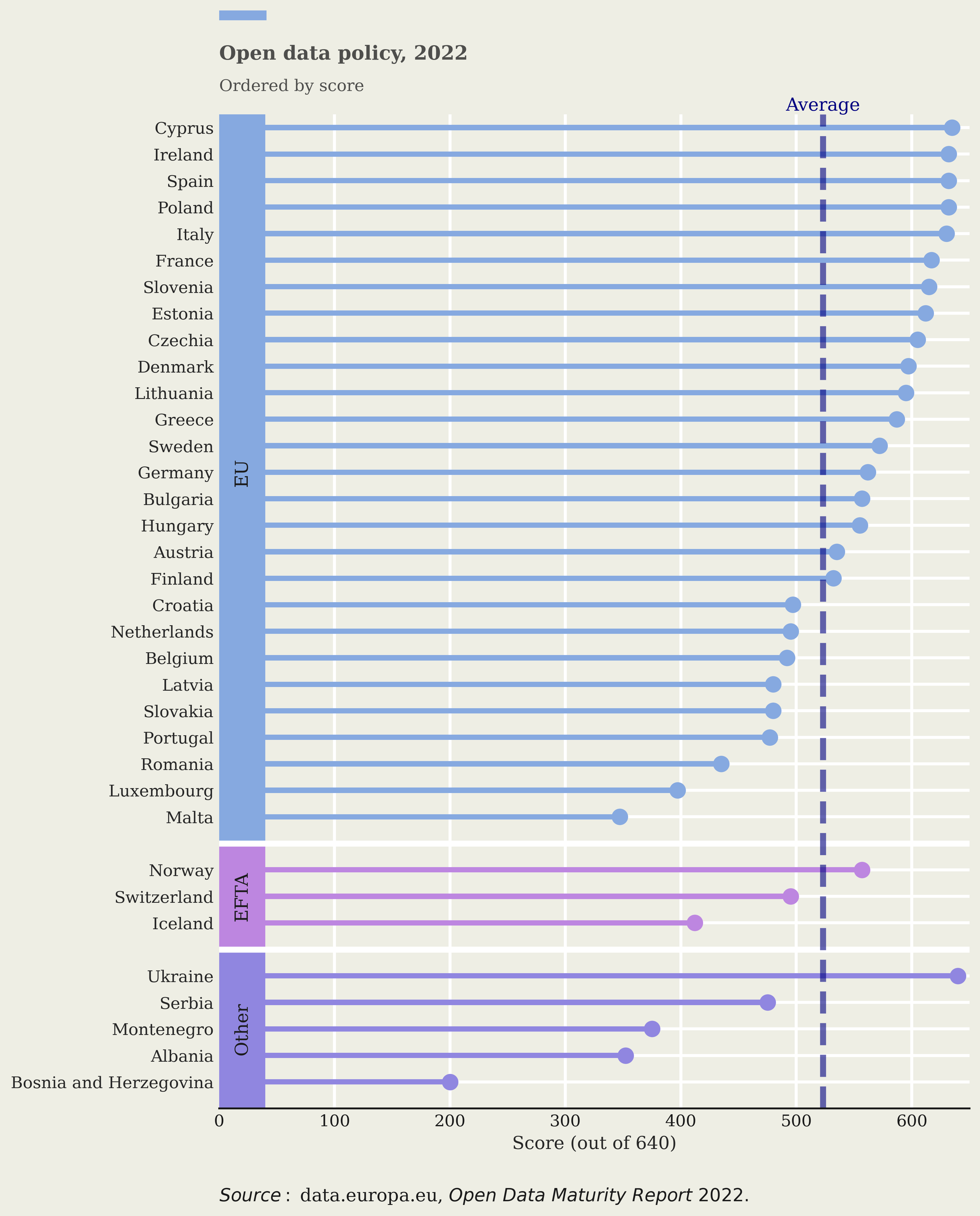

To elaborate on the policy dimension, this data story features the perspectives of Estonia, Italy and Poland (see Figure 1 on the ranking of the country scores). These three Member States share interesting best practices and reflections on their performance in the policy dimension. In this data story you will first find an overview of the policy dimension. Then it presents the successes and improvement points of the three featured Member States, analysing their common themes and differences. Lastly, it explores the specific indicators of policy framework, governance of open data and open data implementation in more detail, to highlight best practices.

Figure 1: Overview of the ODM policy dimension 2022 country scores

The policy dimension in a nutshell

In general, open data policies can be thought of as a system of laws, regulatory measures, courses of action and guidelines established by governments to promote the accessibility and sharing of public sector data. The general purpose of open data policies is to remove barriers to data access, encourage data reuse and enable innovation by allowing citizens, businesses, researchers and other organisations to use the data for various purposes.

The European Commission’s policies for data focus on generating value for the economy and society through the reuse of public sector information. Specifically, the open data directive, which had to be transposed into national law by July 2021, guides EU Member States in making public sector data and publicly funded data reusable. The directive specifically aims to stimulate the publication of dynamic data and the use of application programming interfaces. It also limits exceptions for charging reusers more than the dissemination (marginal) cost of public data resources. Moreover, the directive mandated an implementing act for high-value datasets, which followed in December 2022 (to be implemented by 2024) and made six categories of data available for reuse with minimal legal and technical restrictions and free of charge. Further to the open data directive, other legislative measures aim to boost data sharing and the single market for data but are not specific to open data. For example, the Data Governance Act aims to ‘increase trust in data sharing, strengthen mechanisms to increase data availability and overcome technical obstacles to the reuse of data’. Additionally, the proposed data act would introduce new access and use rights on data to make more data available for use in line with EU rules and values.

The policy dimension of ODM assesses the maturity of national open data policies. It investigates national governance models and the measures applied to implement policies and strategies in line with EU open data policy objectives. This dimension assesses several criteria grouped into three indicators, as follows.

-

Policy framework. The extent to which actionable open data policies and strategies are in place to incentivise open data reuse in both the public and private sectors.

-

Governance of open data. The extent to which public sector bodies have governance models and regular coordination activities in place to ensure the publication of open data at all government levels and to support local and regional open data initiatives.

-

Open data implementation. The extent to which data publication plans, implementing processes and monitoring measures are in place to enable open data initiatives.

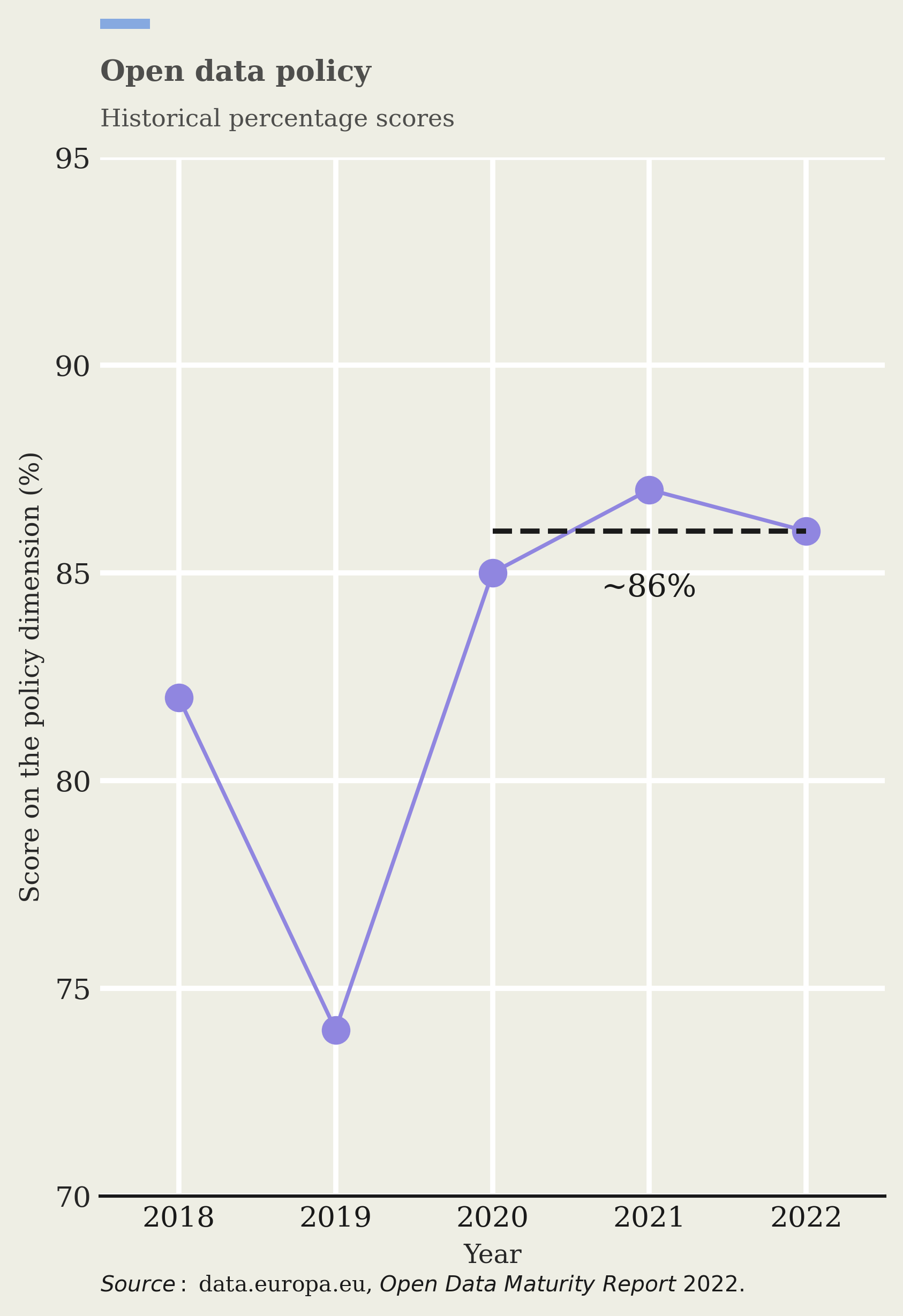

Countries are scored on the basis of a list of questions relating to each indicator, with the scores added together to provide a total for the dimension (full details of the scoring are found in the ODM methodology paper). The policy dimension was introduced in 2018 and is now the most mature dimension of ODM, having the highest average score among the four dimensions for the EU-27. The average score for the EU-27 has been stable over the past three assessments, ranging between 85 % and 87 % in the 2020–2022 period (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Average percentage score for the EU-27 on the ODM policy dimension (2018–2022)

A common strategy for success: continuous monitoring and incremental improvements

The three featured Member States – Estonia, Italy and Poland – all have their own approaches to open data policies. However, three shared principles stand out: (1) adopting an iterative approach, where processes are evaluated and consequentially improved in increments; (2) creating actionable plans; and (3) continuously monitoring how public sector bodies implement the open data policies and what kind of support these bodies need. The individual Member States describe how they implement these principles in distinct ways.

Estonia opts for a collaborative approach to formulating open data policies and strategies involving stakeholders. The national open data team reflects that extensive stakeholder involvement from early in the process is reaping rewards today. These stakeholders include government organisations and representatives from the private sector. This approach treasures inclusivity and transparency. The team regularly consults and involves open data stakeholders and assesses the open data landscape so that policy and strategy formulation are targeted towards the needs of stakeholders and evolve with them. For this purpose, government organisations are evaluated each year on their data maturity. Similarly, private sector stakeholders are also evaluated on their maturity to understand their requirements and needs. The results from the data maturity studies feed into a yearly action plan that follows through to implement the required changes. Continuous monitoring is conducted alongside these efforts, requiring the support and involvement of every level of government.

To further improve its open data policy, Estonia is developing a new methodology aimed at assessing the impact of open data on the economy and society. The goal of this methodology will be to provide a comprehensive view of which sectors are the most impactful when it comes to open data. With the addition of this new methodology, Estonian open data policy could then be fine-tuned to support the data economy.

Italy’s open data policy is based on the Code of Digital Administration, which first came into force in 2005. The code is a single text that unifies and organises rules concerning the digitalisation and digital transformation of public administrations in relations with citizens and businesses. This document also sets out a 3-year plan for such administrations’ information and communication technologies and includes an action plan for open data. The text and its accompanying action plan served as the guidelines for defining technical rules to transpose the open data directive into a national decree. The national open data team believes this structured approach allows Italy to align with EU legislation in a timely manner, and in some cases to be proactive in anticipating new regulations. For example, an Italian decree established in 2011 to define the technical rules for its geo-topographic database put the country in a good position to implement the regulation on high-value datasets as it relates to geospatial data.

In addition to their successes, the national open data team also reflects on opportunities for improving the governance indicator. Currently, responsibilities are distributed among several public administrations, which results in some overlaps and gaps in the division of roles. A related improvement point would be the speedier implementation of policy measures. Even though Italian national policies are aligned with EU provisions, their execution incurs delays in some cases.

Poland puts its good performance on the ODM policy dimension down to three key elements: consistency in action, committed leadership and continuous evaluation. Consistency and commitment create a stable environment where initiatives are carried out and the continuous evaluation means that changes are implemented as needed. The Polish national open data team also highlights that it goes beyond creating the strategy and legal framework. It does this by also providing stable financial support for implementation activities to help realise its policy objectives.

When it comes to improvements, the national open data team points out that Poland’s Open Data Act and 2021–2027 open data programme have been operational for 2 years. The progress of both the strategy and the legal framework is now being evaluated, looking at the impact they have had so far and searching for areas of improvement or adjustment. The evaluation will determine the tasks of the national open data team for the near future. One ambitious challenge the team is considering is the expansion of its network of open data officers. The legal obligation to appoint data officers applies only to ministries, the Prime Minister’s Office and Statistics Poland; in other institutions it is optional. In line with their policy objectives, it would be desirable to extend the network of officers to key central offices and to the local level, especially when it comes to cities.

The policy dimension in detail

In addition to their self-reflections on their overall performance on the policy dimension, the three featured Member States also share their best practices on the three indicators that make up the policy dimension.

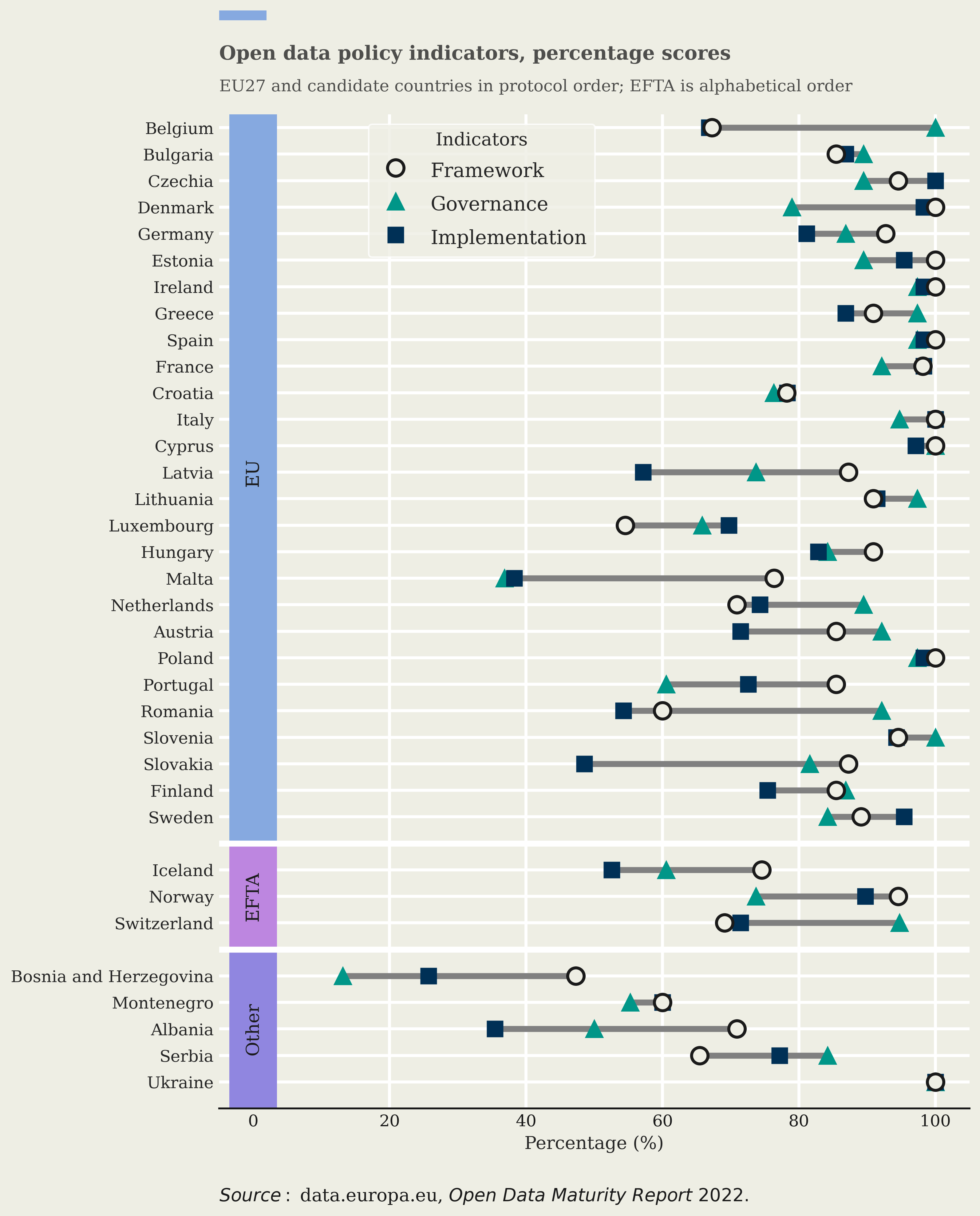

Figure 3 provides a detailed overview of countries’ scores for each policy indicator in 2022.

Figure 3: ODM ranking on the three indicators of the policy dimension in 2022 for all 35 participating countries

-

Policy framework

The policy framework indicator analyses open data policies, strategies and action plans from a national, regional or local perspective. The indicator evaluates the measures in place to support access to and the discovery of specific types of data (such as real-time data, geospatial data and citizen-generated data) and incentives to promote the reuse of open data.

Estonia’s approach regarding the policy framework centres on its open data action plan. This document, which is revised annually, defines goals for the following 2 years. The goals cover several areas, such as the public and private sectors and the research, education and legal domains. Specific objectives are set out for each area, along with key performance indicators for their evaluation and activities needed to reach them. Additionally, Estonia has brought its open data policies together into a single legal framework.

In Italy, the Agency for Digital Italy was responsible for defining binding guidelines to implement the relevant legislative decrees that transposed the open data directive into national law. These guidelines aim to support public administrations in the process of opening their data, covering topics such as metadata profiles, licences and pricing, and data quality. Regarding the licensing framework, the guidelines mandate using the international open creative commons licences CC BY 4.0, CC0 or any equivalent or less restrictive open licence. Lastly, Italy is currently drafting new guidelines on the topic of high-value datasets.

While implementing the open data directive, Poland also brought its policy framework together under a single national legal framework that contains all the key elements, mechanisms and solutions regarding open data. One advantage of collecting all the legal measures in one place is that they do not need to be included in other strategic or operational documents. Strategic and operational measures are in turn collected in Poland’s 2021–2027 open data programme. The national open data team reflects that this division results in an open data ecosystem that is coherent and transparent.

-

Governance of open data

The governance of open data indicators evaluates the structures in place for the publication of open data by public sector bodies at all governmental levels (i.e. national, regional and local). Specifically, the indicator considers the appointment of civil service officials dedicated to open data; the regular exchange of knowledge and experience within the public sector; and regular exchanges between public bodies as open data providers and academia, businesses and citizens as open data reusers.

Estonia has established a Data Governance and Open Data Competence Centre, which has the purpose of promoting an open data culture. The centre is coordinated by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications. Other stakeholders in the competence centre include Statistics Estonia, the State Information System Authority and the Data Protection Inspectorate. The centre offers support and advice to public administrations on data management and assists them with aspects relating to open data, such as identifying datasets, conducting upskilling activities and organising events, among other functions.

In Italy, the national guidelines include recommendations when it comes to roles and responsibilities for open data initiatives run by public administrations. However, the organisational autonomy of each public administration does not allow for a common governance model. Nonetheless, each public administration is advised to set up a special working group dedicated to the data-opening process. The Office of the Digital Transition Manager has an overarching role in matters relating to the digital transformation of public administrations.

Poland uses open data schedules as a key element of its management system. The schedules for opening data are prepared each year by open data officers. These schedules are used as tools for incentivising and motivating the officers to regularly review data in their institutions and for monitoring quality.

-

Open data implementation

The open data implementation indicator evaluates the level of implementation of countries’ open data policies and strategies. Specifically, the indicator assesses whether implementation plans and monitoring measures are in place to enable open data initiatives. It also evaluates the planned activities to support data holders in their publication processes, along with training activities for data literacy.

Estonia monitors and evaluates the progress of national public sector bodies regarding open data. This is done through a yearly data maturity assessment. Based on this evaluation, the national open data team can offer guidance to public sector bodies on various areas, such as strategic coordination, data-management aspects, technical tools and data-quality processes.

To monitor open data policy implementation in Italy, the Agency for Digital Italy has created a public dashboard that tracks the (increasing) number of open datasets on the national portal and the number of administrations that publish open data. Another dashboard measures the quality of metadata published on the national portal. Moreover, a monitoring report on public administrations implementing open data is published each year, weighing the results achieved against the objectives of the 3-year plan.

The Polish open data team highlights the importance of data literacy in achieving open data policy implementation. The team has prepared a modular curriculum of open data courses. The curriculum draws on the experience of the open data team while working with open data officers. The members of the team emphasise that they make it a practice to use the experience and knowledge of the team in this way, such as by writing reports, manuals, guidelines, etc. The team treats popularising knowledge about open data as an important element of its work.

Conclusion

The European data strategy emphasises the ambition of making the EU a leader in a data-driven society. The open data directive specifically stresses the potential of publishing and reusing data from public sector bodies as a tool for boosting innovation and growth, such as through the creation of value-added services and applications. Overall, Europe does well on open data policy, in that this dimension scores the highest on average for the EU-27 among the four dimensions evaluated by the ODM report in 2022. Nonetheless, progress on ODM has plateaued in recent years.

Estonia, Italy and Poland offer examples of best practices from their differing approaches to open data policy. All three featured Member States actively support their policy objectives with actionable plans and put mechanisms in place to monitor their progress. They emphasise the importance of involving stakeholders in the policymaking process and adapting to legislative and technical developments in the open data landscape. Steps are typically taken iteratively, with a view to achieving incremental improvements over time. These experiences and insights can be a source of new ideas and practices for other countries to use to help improve the implementation of their national open data policies.

Interested in learning more about open data maturity? Read the ODM report for more insights into the 2022 assessment, view our interactive ODM dashboard and explore the related courses on the data.europa academy website. If you are interested in the other ODM dimensions, stay tuned for the next instalment in this series. Keep up to date by subscribing to our newsletter and following data.europa.eu on social media.

Many thanks to Ott Velsberg (Estonia), Antonio Rotundo (Italy) and Joanna Malczewska (Poland) for their contributions to this data story on behalf of their national open data teams.