Economic Forecasts and Policy Responses to the “Great Lockdown”

The Coronavirus led many countries to implement restrictive measures such as national quarantines and the closing of workplaces, triggering a severe economic crisis. This story takes a closer look at the existing global financial and healthcare infrastructure, but also at new financial measures taken by national and European institutions.

To complement the initiatives mentioned in the story, the European Data Portal created two interactive visualisations: Unemployment and GDP growth and global financial measures.

To slow down the spread of the COVID-19 virus, most countries around the world have implemented restrictive measures (for more information read our data story on governmental measures), such as national quarantines, the closing of workplaces, and international travel bans. These measures have already had severe economic consequences for the global economy, e.g., the massive reduction in air traffic discussed in another data story. A fair share of economic activities is facing challenging times, and many have been put on hold. As a consequence, national economies and the global economy are struggling. The recession triggered by the “Great Lockdown “that we are facing today is expected to become the largest economic downturn since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The developments of the crisis and the economy are hard to predict as this is the first time that large parts of the global economy are actively shut down by governments. Moreover, the uncertainty about the epidemiological characteristics of the virus, the effectiveness of the restrictive measures, and the development of a vaccine make economic forecasting even harder.

To mitigate the effects of the Great Lockdown, specific COVID-19 related financial measures – in addition to pre-existing policies – are considered at national, European and global level. In this data story, we showcase available datasets and initiatives that can help economists to research the extent to which existing financial and healthcare infrastructure in combination with the COVID-19 specific financial measures can help soften the blow of the Great Lockdown.

The current outlook

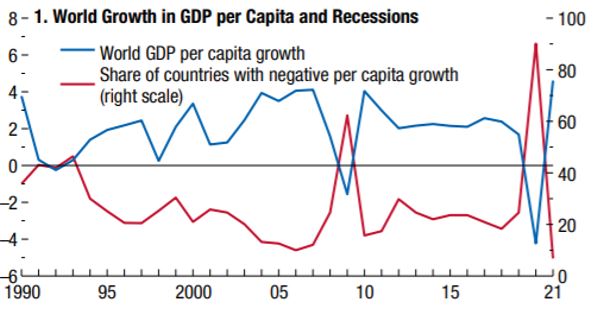

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated in their April “World Economic Outlook” a global economic drop of 3 percent of GDP per capita in 2020 (see figure 1) under the assumption that in most countries the pandemic peaks in the second quarter and withdraws in the second half of this year. However, if the economic downturn is controlled and stabilised during 2021 with the help of policymakers, a global economic growth of 5.8 percent can be expected next year.

Figure 1: World Growth in GDP per Capita and Recessions by IMF

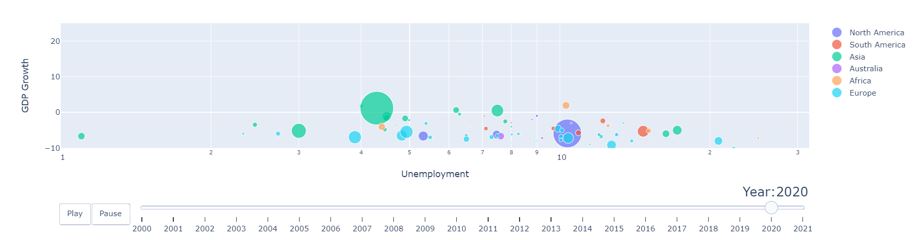

To achieve a better understanding of the impact of the Great Lockdown on employment, the European Data Portal for COVID-19 editorial team created a moving interactive visualisation of the GDP growth and the unemployment rate between 2000-2021. The visualisation, based on the IMF April World Economic Outlook data, shows a great drop in GDP growth and increase in unemployment in 2020 as can be seen in the screenshot presented in figure 2.

Figure 2: Interactive visualisation, created by EDP for COVID-19 editorial team, of world GDP growth and unemployment rate, based on IMF data. Last updated 11 May 2020.

How prepared we were: the financial situation pre-crisis

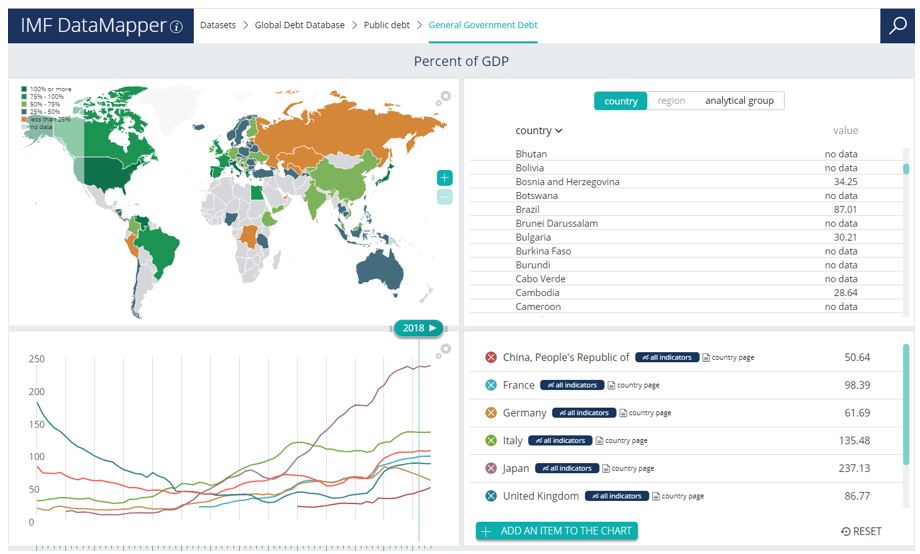

A closer look at historic numbers and the preparation of countries is useful in order to estimate the impact that the Great Lockdown has on national economies. The countries’ state of economic health prior to the crisis can be inferred from a series of proxy economic elements such as social safety nets, national debt levels, and other supporting policies in case of recessions. Looking at statistics of the national debt of European countries, we can see which countries have a national debt of more than 100% of their GDP in 2019, making it more expensive for them to borrow money for national support during this crisis since interest rates may likely increase. A high national debt could lead to more consumer saving (instead of spending/investing) when people expect taxes to increase as a way for the government to pay off the debt. In the long term, a high national debt has negative effects on exchange rates and the interest rates for the private sector and eventually for consumers. Also, there is the fear that excessive government debt can lead to a sovereign debt crisis, as seen in Greece and other Eurozone countries. To get a better understanding of the debts of governments, IMF used their IMF DataMapper to visualise the general government debt until 2018 in Europe and other parts of the world. It shows that the south European countries, Japan, and North America already have a relatively high governmental debt as percentage of GDP, see figure 3.

Figure 3: A screenshot of IMF’s DataMapper of the General Government Debt until 2018.

How prepared we were: preparedness for health emergencies

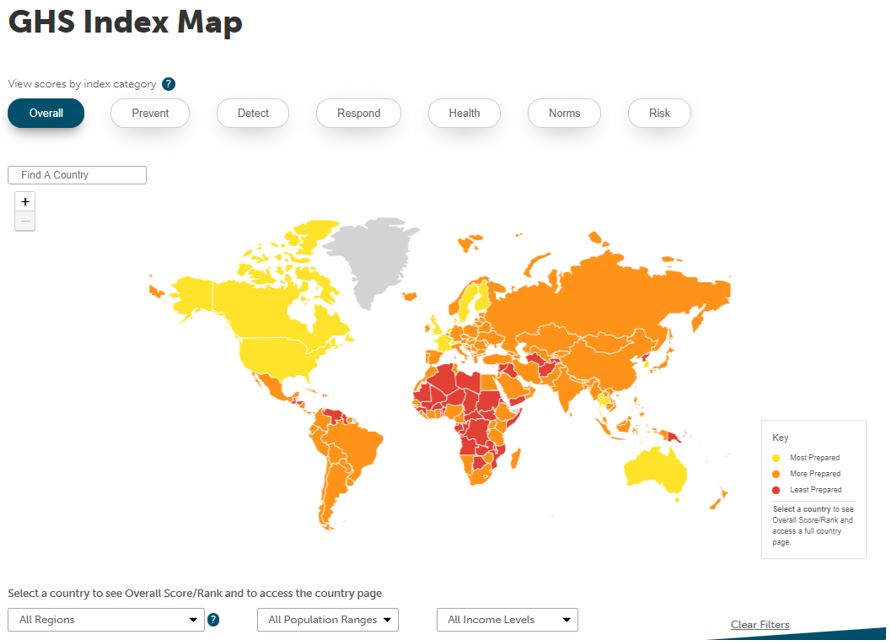

In October 2019, the Global Health Security Index was established, which is a comprehensive assessment of the preparation for epidemics and pandemics for 195 countries. The GHS Index is a project of the Nuclear Threat Initiative and the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, and was developed with the Economist Intelligence Unit. They create a framework, organised across 6 categories, 34 indicators, and 85 sub-indicators to assess a country’s capability to prevent and mitigate epidemics and pandemics. The index already showed in October 2019 that collectively, international preparedness for pandemics was very weak. Figure 4 below, shows the interactive GHS Index Map, which visualises the levels of preparedness per country in the world. It is important to note that the level of preparedness does not entirely correlate with the actual performance of a given country once the present pandemics arrived.

Figure 4: Global Health Security Index Map

How impact is mitigated: COVID-19 specific financial measures

In addition to existing social safety nets and other policies that are in place, there are specific COVID-19 related financial measures taken on European, regional, and national levels. These fiscal and monetary measures are being introduced by governments and institutions to support healthcare systems, protect the jobs and incomes of people, as well as to soften the blow to the economy at large. On a European level, the European Central Bank (ECB) implemented a response to COVID-19 consisting of three mutually reinforcing complementary components. The temporary Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) constitutes the first component. It foresees purchases at a volume of €750 billion of eligible private and public securities throughout this year, and longer if needed. Secondly, the response consists of Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTROs) and a set of collateral easing measuring to ensure that banks remain reliable carriers of monetary policies and continue to lend money. Finally, the ECB offers liquidity to banks over longer horizons at a negative rate, without any conditions attached, to stimulate the economy.

To get a better understanding of countries’ national financial responses, the IMF provides a summary of the key economic responses governments are taking to limit the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in their Policy Tracker. The IMF Policy Tracker offers fiscal, monetary, macro-financial, exchange rate and balance of payment measures taken by 193 economies worldwide (last updated April 24, 2020). Similarly, the Yale Program on Financial Stability, the Institute of International Finance (IIF), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are tracking financial policy responses.

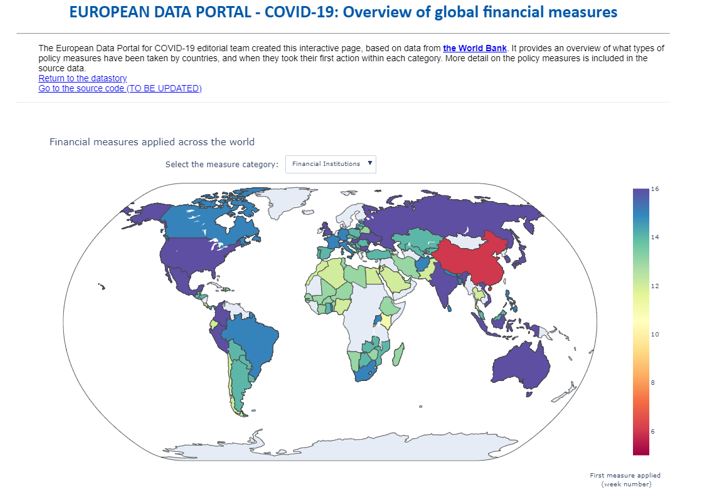

The World Bank compiled a dataset using publicly available information collected by the World Bank and COVID-19 financial response trackers maintained by several entities (such as the IMF Policy Tracker, the Yale Program on Financial Stability, IIF, and OECD). The dataset tracks measures that governments have taken to support their financial sector in response to COVID-19. Policies are classified according four main categories: liquidity/funding, financial institutions, financial markets and payments systems (which are referred to as the “Level 1 policy”). Each category has different sub-categories (referred to as “Level 2 policy measures”) which are summarised below:

- Liquidity/funding:

- Liquidity measures, e.g., refinancing

- Policy rate measures, e.g., cutting interest rates

- Asset purchases, e.g., lifting purchase limits

- Financial institutions:

- Prudential measures that e.g. allow banks to temporarily operate below “normal levels” of capital and liquidity

- Measures to support borrowers, e.g., grant schemes

- Measures to safeguard integrity of financial institutions

- Operational continuity measures, e.g., evaluation of risks for operational continuity

- Crisis management measures

- Financial markets:

- Market functioning measures, e.g., prohibition of short-selling

- Public debt management measures

- Payments systems

The interactive map below (see figure 5) is created by the European Data Portal. The different first level policies and the calendar week when they were first introduced are visualised for countries in Europe.

Figure 5: Screenshot of interactive visualisation of Worldbank Financial Measures data by the EDP for COVID-19 editorial team

As can be seen from the visualisations above, countries are taking actions to ease the economic impact of the crisis. However, we are still in the middle of the Great Lockdown, making it difficult to predict the course of the pandemic and the exact impact it will have on the global and national economies. A heavy economic crisis seems inevitable and national governments and institutions work hard to mitigate its consequences. The data and initiatives presented in this story provide insights in the situation before the crisis and the measures taken by national policy makers to stimulate the economy and help the sectors that are hit the hardest. Economists – with their expert knowledge – can use these and many other available data and related initiatives to draw their conclusions so they can advise and guide decision makers to help soften the blow of the “Great Lockdown” on our economy.

Looking for more open data related news? Visit the EDP news archive and follow us on Twitter, Facebook or LinkedIn.